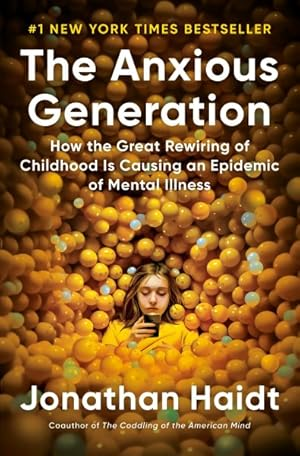

Subtitle: “How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness”

On the one hand, I probably write 4-5 music reviews for every book review. On the other, neither are actually reviews. More than a few times, I’ve been asked, “So, what exactly qualifies you to be a music critic?” My answer: “I’m not a music critic. I’m a music liker. If I like a new release, I write about it. If I don’t like it, I just don’t write anything.” I pretty much take the same approach with books. (Although I guess it may be more accurate to say that if I don’t like a book, I just don’t… finish it.)

I not only like this book, I’m a big Jonathan Haidt fan. (Here’s the link to my “review” of his 2020 book The Coddling of the American Mind – http://thoughtsoncharacter.com/the-coddling-of-the-american-mind/)

In any case, my definition of a great book is one that compels me to keep thinking hard about its message long after I have closed its front and back covers. Here are ten points that have kept me thinking since I finished The Anxious Generation:

1. In his introduction, Haidt names the two biggest mistakes we’ve made as a culture: “overprotecting children in the real world (where they need to learn from vast amounts of direct experience) and underprotecting them online (where they are particularly vulnerable during puberty).”… Later in the book, he writes, “We are overprotecting our children in the real world while underprotecting them online.” Yup.

2. In the same paragraph, he lists four reforms he argues will lay the foundation for a healthier childhood:

- No smartphones before high school

- No social media before age 16

- Phone-free schools (during the entire school day)

- More unsupervised play and greater childhood independence

3. “Children born in the late 1990s were the first generation in history who went through puberty in the virtual world. It’s as though we sent Gen Z to grow up on Mars when we gave them smartphones in the early 2010s, in the largest uncontrolled experiment humanity has ever performed on its own children.” [Underlining is mine.]

4. The problem with social media for pre-age-16 kids is that… “Life on the platforms forces young people to become their own brand managers, always thinking ahead about the social consequences of each photo, video, comment, and emoji they choose. Each action is not necessarily done ‘for its own sake.’ Rather, every public action is, to some degree, strategic. It is, in Peter Gray’s (Note: a Boston College psychologist) phrase, ‘consciously pursued to achieve ends that are distinct from the activity itself.'”

5. Why is this a problem? He poses a dynamic of two modes: Discover and Defend.

– Discover mode: “a behavioral activation system (or BAS) that turns on when we detect opportunities.”

– Defend mode: a behavioral inhibition system (BIS) that kicks in when threats are detected.

6. Haidt explains that a healthy childhood featuring healthy amounts of autonomous and unsupervised play naturally fuels a Discovery mode mindset leading to positive relationships and an ability to cope and handle risks. However, recent trends of overprotective parenting and early exposure to online social media platforms tend to fuel more of a Defend mode. So what? Haidt, a college professor, observes, “As soon as Gen Z arrived on campus, college counseling centers were overwhelmed. The previously exuberant culture of Millennial students in Discover mode gave way to a more anxious culture of Gen Z students in Defend mode.”

7. Returning to the model of “antifragile kids” that he explained in The Coddling of the American Mind, he argues that “overprotected children are more likely to become adolescents who are stuck in defend mode. In defend mode, they’re likely to learn less, have fewer close friends, be more anxious, and experience more pain from ordinary conversations and conflicts.”

8. He spends considerable time exploring the effects that parental over-protection (Or, as he calls it, “safetyism”) and early social media engagement have on both girls and boys. He observes, “The more time a girl spends on social media, the more likely she is to be depressed. Girls who say that they spend five or more hours each weekday on social media are three times as likely to be depressed as those who report no social media time.”

9. Much of what Haidt writes reflects a view I have held for a long time: Just because we might successfully force kids to put their phones down, that does not mean they stop obsessing about the next chance they will have to pick them back up again. Forbidding them during class time simply does not go far enough. Not only have I watched countless high school students walk, talk, and text while they’re moving to and from class, they often end up being late as a result. But more than that, their train of intellectual thought is constantly interrupted. Rather than ponder their teacher’s interpretation of King Lear as they head into biology, they’re desperately texting Johnny to see what the gang is doing after school lets out. And beyond that… “When students are allowed to keep their phones in their pockets, phone policing becomes a full-time job, and it is the last thing teachers need added to their workload. Many of them eventually give up and tolerate open use. As one middle school teacher said, ‘Give teachers a chance. Ban smartphones.'” Yup, yup, & yup.

10. Haidt kicks off his 12th and final chapter — “What Parents Can Do Now” — with a captivating 3-sentence paragraph:

In The Gardener and the Carpenter, the developmental psychologist Alison Gopnik notes that the word “parenting” was essentially never used until the 1950s, and only became popular in the 1970s. For nearly all of human history, people grew up in environments where they observed many people caring for many children. There was plenty of local wisdom and no need for parenting experts.

Haidt goes on to explain the gardener vs. carpenter dichotomy:

Gopnik says that parents began to think like carpenters who have a clear idea in mind of what they are trying to achieve. They look carefully at the materials they have to work with, and it is their job to assemble those materials into a finished product that can be judged by everyone against clear standards…. Gopnik says that a better way to think about child rearing is as a gardener. Your job is to ‘create a protected and nurturing space for plants to flourish... Amen.

BONUS: “There are three ways to improve recess. Give kids more of it, on better playgrounds, with fewer rules.”

Onward, Malcolm Gauld