Although no one would characterize adolescence as a one-size-fits-all phenomenon, social scientists are in general agreement that it has three phases:

Early (10-13): physical body and hormonal changes… lots of black & white thinking… desire for peer approval begins to compete with parental praise as a primary motivation.

Middle (14-17): full tilt puberty… strong romantic and sexual desires… that delayed frontal lobe thing triggers delayed gratification issues… peer approval now commonly overpowers parental authority.

Late (18-21+): enhanced impulse control… future-oriented… self-conscious identification of and alignment with values.

That’s what the social scientists tell us. My 45-year experience as a field technician has caused me to assume and expect two teenage conditions:

- Emerging teens are conflicted between what is right versus what is cool.

- Older teens can get locked up in self-absorption.

As educators (and parents!), our job is to help kids sort out the former and transcend the latter. Toward these ends, an inspiring school culture is indispensable.

Such a culture demands the absence of some elements (bullying, prejudice, cheating, indifference)… and… the presence of others (respect, creativity, effort, inclusiveness).

Consider bullying: Even if a school manages to make bullying absent, it does not necessarily follow that an uplifting esprit de corps will be present.

One need not look very hard to grasp why all 50 of the United States have enacted anti-bullying legislation:

- The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) shows that 1-in-5 public school students report being bullied. (41% of those bullied live in fear of it happening again.) Incidents among girls approach 1-in-4.

- The CDC reports that over 30% of all middle school students have experienced cyber-bullying.

- A 2017 GLSEN National School Climate Survey shows that 60% of America’s LGBTQ students feel unsafe in school due to their sexual orientation.

A recent University of California study evaluates and ranks 53 U.S. anti-bullying programs. The very fact that there are 53 anti-bullying programs – The study did not stipulate how many other programs it simply chose not to evaluate. – ought to be seen as a siren call for lack of consensus. It makes you wonder: Does this proliferation of programs fuel the solution or the problem?

Contemporary anti-bullying programs tend to fall into a “make it absent” default zone, one heavy on identifying and penalizing behavioral violations. Some even reflect a scorched earth approach where even teasing, a normal part of adolescence, is verboten. Hence, it is perhaps not surprising that conventional social & emotional learning (SEL) state standards are commonly heavy on compliance, obedience, and cooperation and light on ambition, chutzpah, and pursuit of dreams. Maybe we need to flip the telescope around from What to do about bullying? and refocus it on What to do about inspiration?

Obviously, schools cannot serve as providers of transformative experience when students spend any time feeling physically threatened, publicly humiliated, or virtually maligned. At the same time, “safe” is a pretty low bar. (As a country, are we OK with bragging about the safety of our schools? I mean, shouldn’t that be a given?) Kids need to jump higher if they are to test their abilities, hopes, and dreams.

For at least two generations – from New Math to No Child Left Behind – we Americans have demonstrated that we love thinking about educational reform more than we love doing it. Meanwhile, as national confidence continues to slide, here’s how the whole scene looks to our students:

They care more about what I can do than about who I am.

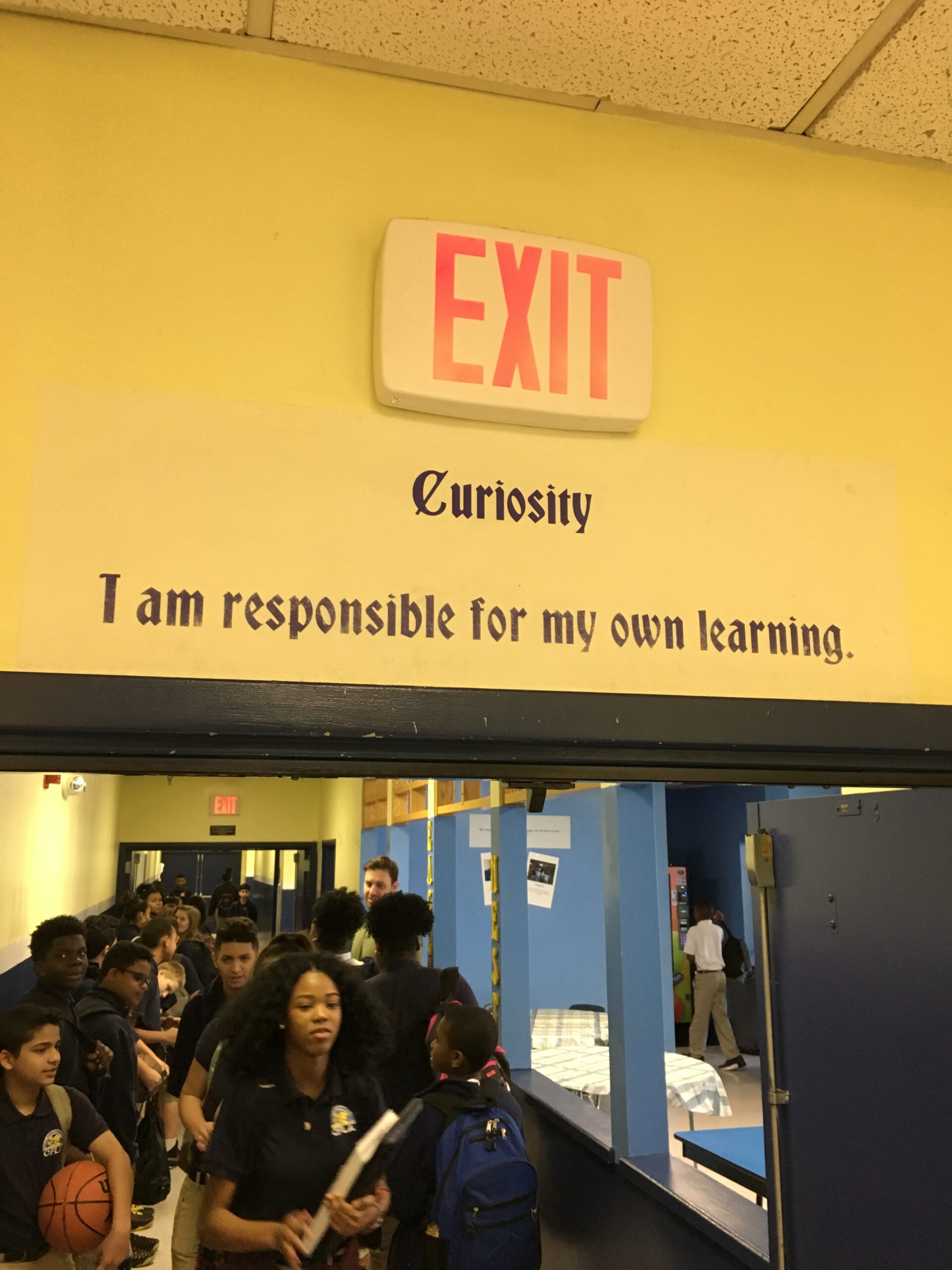

How do we reverse this? By creating school cultures that value:

Attitude over Aptitude – Effort over Ability – Character over Talent.

For nearly 25 years, a small cohort of public schools in rural Pennsylvania has offered a revised homeroom model called the Discovery Process where students consistently:

- Feel more included and have a sense of connection to the school and to one another;

- Demonstrate better coping skills in day-to-day interactions with both peers and adults;

- Benefit from better rapport between younger and older students:

- 5th and 6th graders look up to 7th and 8th graders rather than fear them.

- 7th and 8th graders rise to expectations as positive role models and leaders.

Furthermore, teachers and administrators report advancements in learning that they attribute to fewer disciplinary distractions and sharper concentration during class time.

Sometimes called an old-fashioned idea ahead of its time, Discovery Process students meet daily in mixed-aged homerooms where they share a common character language and engage in teams in core activities ranging from intramurals to performing arts to campus clean-ups. The premise is simple: Character is what matters most in both bad and good times. And as one Pennsylvania school principal says, “We used to have a lot of fights, but since starting this program, they have basically stopped. And as for bullying, we don’t even talk about it. It just doesn’t happen here anymore.”

So, instead of bullying, they talk about inspiration, learning, and maximizing potentials. Isn’t that the way school should be?

Onward, Malcolm Gauld