Prostate Cancer in the Rear View Mirror –

My Story

by

Malcolm Gauld

|

The Diagnosis

“You have prostate cancer.” (February 2011)

BRUNSWICK, ME – My son and I were browsing the racks at Borders Books (Remember Borders?) when my cellphone buzzed. Caller ID popped up the name of the local urologist who had recently performed my prostate biopsy. [Long story short: During a routine annual check-up, my PSA test (Longer Story Shorter: A “Prostate Specific” blood test designed to indicate presence of prostate cancer) showed that my “numbers,” although quite low, had spiked a bit. Erring on the side of caution, my primary care doctor had suggested that I have a biopsy.] My anxiety spiking (more than) a bit, I frantically sidled over to a more isolated aisle of the non-fiction section in hopes of learning the verdict amid whatever privacy could conceivably be squeezed out of your average big box store.

“Hello,” I whispered.

“Hi, Malcolm,” he replied. “I have the results of your biopsy and would like to discuss them with you in my office.”

Me: “Doctor, I basically live on the phone. Please tell me now.”

Doctor: “I really prefer to discuss all test results in the privacy of my office.” From there we went back and forth until he ultimately agreed to acquiesce to my persistence.

Then he paused and calmly said, “You have prostate cancer.”

With my son now next to me, anxiously waving the book he had selected for purchase, I responded as casually as I could, thanking the doctor for the information. We made an appointment to talk in person, the doc concluding with something to the effect of, “A very, very small amount of cancer has been detected. Thankfully, this gives you a wide range of encouraging options to consider which we will discuss when you can come in.”

As though in a trance, I managed the motions of the Borders check-out process at the register and then drove home on robotic auto-pilot, remaining in trance-mode for the next few hours. After my wife Laura and I both shed some tears in our living room, I proceeded to engage in some serious Googlage into the wee hours to learn as much as I could about this scary affliction that had previously visited only with a category of persons my sub-conscious had filed under “other people.”

I’d had a fair amount of experience with cancer when the pronoun involved was him, her, he, or she. However, a doctor can get your attention when he turns the whole thing around to you.

A few days later, my doctor explained that my biopsy had detected a tiny amount of cancer in one of the eighteen microscopic samples that had been surgically extracted from my prostate. If you are familiar with the whole prostate cancer thing, it may interest you to know that my biopsy revealed a Gleason Score of 6. If you have no idea what that means, you may have some sense of how I felt. The more my doctor kept telling me that a 6 was a good thing, the more I couldn’t get it out of my head: If 10 is the worst, how could being on the wrong side of the halfway mark be good? (Truth be told, I still don’t get it.)

|

The Dilemma(s)

As a new member of the prostate cancer club, I learned that my future – and whether “future” meant distant or immediate was troublingly unclear – involved three overall options:

1) Radiation;

2) Surgical removal (Referred to as Radical Prostatectomy);

3) Keep a close eye on it (Sometimes called “Active Surveillance” or “Watchful Waiting”).

To compound the decision-making challenge, I felt confronted by a seemingly endless array of choices to make within the construct of each of these three separate options. For example, you can have your radiation the old-fashioned way… OR… You can have these weird “seeds” implanted in your body that reportedly scurry around your innards like voracious cancer-eating Pac Men. You can also go old-fashioned with the radical prostatectomy and have your surgeon perform the procedure with his (hopefully) sure and steady hands (an approach which, in turn, involves further choices regarding preference of point-of-body entry)… OR… You can choose to presumably reduce the potential for human error and have… a robot do it!

Spiraling further down the compounding theme… While you, the patient, are sorting out these three options, you soon realize that yet another layer of complication is added to the chess game once you grasp the fact that each and every choice has a fairly cut-and-dried up- and down-side. For example:

– While surgery offers excellent prospects (but not a guarantee) for completely removing both the prostate and the cancer it carries, it can also bring troubling side effects like incontinence and impotence. (And that’s “will” not “can.” In other words, you will have both, at least for a while, if not permanently. Your incontinence might heal in a few months, but you should expect the impotence to last for two years, if not… forever.)

– While radiation is less invasive than surgery, it’s harder to know if the cancer was completely eradicated. (Did I mention that PSA tests are famously unreliable?)

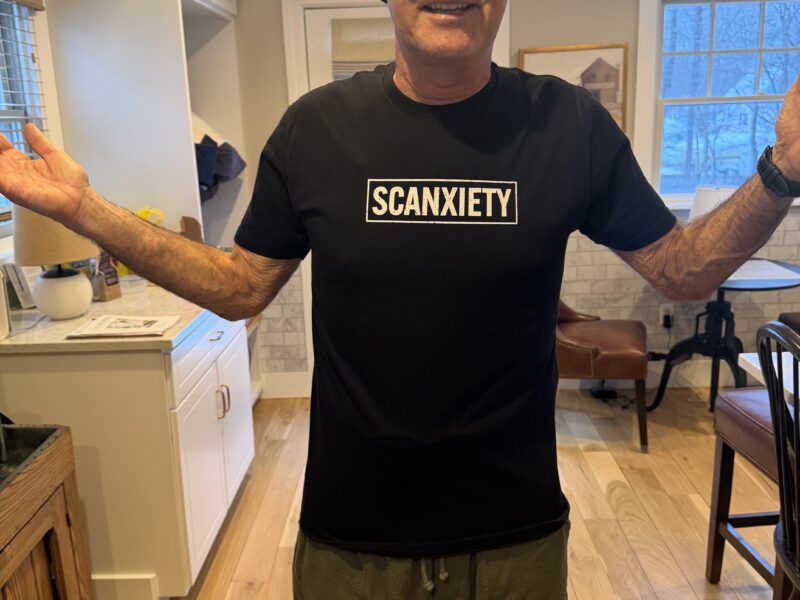

– While active surveillance is presented as the only non-invasive option, I can tell you from first-hand experience that I don’t ever recall a time when my psyche was ever as heavily invaded! Between those quarterly check-ups you’re always wondering, What’s it doing now? Nothing like a PSA test every three months to trigger an anxious emotional roller coaster.

Even if you are able to eliminate one of the three options from your thinking, you can’t escape weighing the values of the seemingly endless combinations of up- and down-sides. For example, surgery, unlike radiation, offers the possibility of two bites of the proverbial apple. Specifically, if the cancer returns after your surgery, you can then take a shot with radiation. However, if you go with radiation and it proves unsuccessful, you generally cannot follow it with surgery. (While assuming that you have by now figured out that you do not want to rely on me as a credible medical authority, my layman’s understanding is that radiation does such a number on the surface of the prostate that it renders it inoperable.)

Before long, I was feeling like a dazed contestant on Let’s Make a Deal with my doctor starting to remind me of Monte Hall. (If you get the cultural reference, you are in prostate cancer’s age range. If not, you’re watching way too many TV reruns.) At least there were no anxious catcalls of advice from the crowd as I prepared to select Curtain #1, #2, or #3.

One of the helpful moves my doctor made was to urge that Laura be included in our discussions. Not only could we share thoughts and feelings and lean on each other, I didn’t need to explain everything all over again each time I came home from appointments.

I also learned that prostate cancer grows very slowly. Every doctor I consulted with said, “A lot more men die with prostate cancer than of it.” One even said, “You might even be able to go 15 years before you have to do anything about it.” He then balanced this observation by noting that I was relatively young (57 at the time of diagnosis), in perfect health, in excellent physical condition for a person my age and thus, an ideal candidate for surgical removal.

|

The Decision(s)

Early on, a close friend of mine who had lost her husband to cancer said something to me that turned out to be truly prophetic: “You are about to find that a lot more people love you than you thought. You are also about to receive a great deal of advice, and some of it will be contradictory.”

Right away I found both points to be true. Since my diagnosis over three years ago, I have been overwhelmed by the outpouring of support from friends, acquaintances, and total strangers. People seemed to come out of the woodwork. For example, a college friend, with whom I have only spoken once or twice during the past four decades, appeared and referred me to a wonderful doctor who ended up serving as my personal guide through this experience.

At the same time, the amount of advice I received often seemed impossible to absorb and organize in my mind. Several people told me that the Internet would drive me crazy, scare me to death, or both. Yup. I basically stopped looking at it.

After a while, I also found myself steering clear of people who absolutely “knew” what I should do. I learned to spot them by the staunch ideologies worn on their sleeves. They tended to come at me with uncompromising pronouncements like:

– “I can’t imagine why anyone would choose radiation over surgery.”

– “As soon as I heard the “C” word, I had the doctor take it out that day.”

– “Watchful waiting is for wimps.”

I came to realize that one’s chosen course of action is a deeply personal decision, and I found myself drawn to people who felt likewise regardless of what course of treatment they had chosen to adopt.

During this time I also began to perceive a sharp divide between men and women regarding their approaches to cancer. Women invariably seemed far more open with their medical and health issues than men were. Whether participating in a Run for Breast Cancer or sporting pink lapel ribbons, women didn’t emanate the secrecy that shrouds men and prostate cancer. On more than a few occasions I came across longtime buddies who had experienced prostate cancer, and I had never known it. (At my 40th high school reunion, on the second fairway of a golf course, three of us in the same foursome were more than a little surprised to discover that we shared club membership in common.) For sure, I have never been accused of being all that open with my feelings either. In the end, I can’t say how open the average guy should be about his prostate cancer, but I can say that I was struck by the difference men and women seem to reflect when it comes to living with their respective cancers. Part of the reason I am writing this piece at all is because I had hoped that some open sharing might be useful to others in this position. I would say that it’s the women I have known with cancer who have taught me to see it this way.

Come decision time, I decided to trust my Maine doctor who had performed the original biopsy. Perhaps the clincher for me was when he said something to the effect of: “Let me put it to you this way, your cancer is so low right now that anyone who would operate on you would be doing it for the money.”

(Let me digress with some full disclosure. By this point, my mind was swimming with a massive case of T.M.I. I can’t promise you that my doctor said those exact words. I only know that that was my take-away. Could it have been something I wanted to hear? Sure. While I have encountered fellow prostate cancer club members with horror stories about their doctors, I am grateful to report that that really isn’t part of my story.)

So, I embarked upon a program of active surveillance that found me visiting my doctor every three months with urine samples, PSA blood tests, and physical examinations. After the biopsy that initially detected the cancer, I have since had two additional biopsies and an extensive MRI. The MRI may have been less painful, but it lasts for the better part of an hour.

Interestingly enough, my second biopsy (a year after the first) showed zero samples of cancer, leading some family members and loved ones to incorrectly conclude that I was in remission. (Word started getting around that “Mal’s cancer is cured!”) Not true. That second biopsy merely showed that the amount of cancer was so low that it wasn’t detected with this particular round of needles.

How to describe the biopsy? (Beyond my view of it as the ten most unpleasant minutes a guy can experience?) One analogy that might help explain the biopsy is one of those old spy movies where there is a guy with a gun in the room and his adversary is crawling around above the ceiling tile. Unable to see the adversary, the man with the gun starts firing away into the ceiling – either randomly or in some kind of pattern – in the hope that one of the bullets will hit pay dirt and make contact with the invisible target on the other side of the ceiling tile. In the case of the biopsy, the doctor’s “gun,” after entering your innards, repeatedly stabs into different sections of the prostate (an organ about the size of a walnut) with the hope that one or more of the 12 or 18 stabs will come up with some trace of cancer if there is indeed any cancer present in the prostate. Not only is it theoretically possible for cancer to exist and have none of the needles find it, this happens.

In any case, after biopsy #2 I was feeling so good that I almost forgot about the whole cancer “thing” for a while. Then, two years (and a new doctor) later (March 2014), biopsy #3 revealed three samples of twelve that contained very small amounts of cancer. Technically, I was still a candidate for active surveillance. (My doctor: “My limit is four. If four or more samples show cancer and you want to stay with active surveillance, you need to get another doctor.”) However, back in the very beginning, when I was first diagnosed, I had adopted an “if/then” strategy: If a future biopsy revealed three or more cancerous samples, then I would have a radical prostatectomy. Dr. Francis McGovern, my doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, asked me if I wanted to think about it for a while. I said, “I already have thought about it… for three years. I would like to have the surgery at the earliest possible date.” A month later, on May 12, 2014, I found myself lying on his operating table at Mass General.

|

The Surgery

May 2014 (BOSTON) Why his operating table… with so many others to choose from?

Amid all the varied and sometimes contradictory advice I received, there was one piece that was served up consistently. As one friend said, “Go with a doctor who did four or five of them… last week.”

My friend’s advice stands to reason. Imagine a baseball game with the pitcher getting knocked out of the box. Looking for a replacement, the manager doesn’t then yell out to the shortstop, “I’m told you were a hot pitcher back in high school. How about stepping up on the mound to give it a shot?” No way. The manager looks to his bullpen and gives the nod to someone who eats, sleeps, and drinks pitching. So, have your prostate taken out by someone who eats, sleeps, and drinks taking out men’s prostates.

Before giving the final nod to Dr. McGovern, I did explore the option of a robotic prostatectomy. There was this vibe, seemingly coming from the internet and casual conversations, suggesting that the human approach is perhaps passe and that the robotic approach is more modern and certain. Upon further exploration, it also occurred to me that hospitals spend a lot of money purchasing and promoting these very expensive robotic surgery devices because, as another friend said, “They need to feed the beast.”

I went with Dr. McGovern’s human touch for two reasons. First, he had taken me this far and I had come to trust him. Second, he had personally performed over 4,000 radical prostatectomies and could demonstrate hard statistics – Not just industry statistics, but his own statistics – regarding recovery outcomes that either equaled or surpassed all the other options I had considered.

Back on the table… Shortly before I fell under the spell of anesthesia, Dr. McGovern patted my shoulder and softly said, “I’ll bet you’re looking forward to putting this all behind you.” I replied, “Yes, I am.”

The next thing I knew, I was lying prostate (no pun intended) on a rolling bed when I heard someone say, “The surgery has been successfully completed, Mr. Gauld. We’re wheeling you back to the recovery room. Your wife will be there shortly.”

Huh? Somehow, five hours had elapsed since Dr. McGovern offered me his words of assurance.

I remained at Mass General for another day. And just like that, 36 hours after I had arrived, Laura and I were driving back to Maine. My discharge instructions included a cram course on catheter care, dietary restrictions, and a prohibition on any strenuous exercise for 8 weeks with the exception of multiple daily walks.

While the next few days featured some very uncomfortable moments – That first shower was an excruciating ordeal! – each day thereafter got progressively better than the previous one. The catheter was a hassle, for sure. For the daily walks prescribed by my doctor, I would hide the catheter and accompanying urine collection bag in a canvas tote bag. That worked so well that my entrepreneurial side started to think: Hmmm, Designer catheter bags, maybe?… Nah.

The catheter was removed on Day #11 – I mean, it’s not like I was counting or anything – just in time for my daughter’s graduation from college — See photo below of Bowdoin 2014 Commencement — the second alma mater we now share.

The catheter, in turn, was replaced by a big bag of XL-size Depends. (And for every joke I ever told in my younger days about Depends and the men who wear them, I offer 100 mea culpas and a vow: Never again.)

|

The Aftermath

Nearly five months have passed since my radical prostatectomy. My doctor has just pronounced me cancer-free. This determination resulted from two key analyses. First, shortly after the surgery, Dr. McGovern reported the full pathology on my prostate and the skin tissue surrounding where the prostate had been. (While I may not be correct on this, it seems to me that it really doesn’t matter how cancerous the prostate is. The danger lies in the cancer leaving the prostate and entering other organs or parts of the body.) Reviewing the pathology with me, Dr. McGovern said, “I’ve never owned a boat, but if I ever do, I will call it ‘Clear Margins.’ That’s what you now have – clear margins. To use another analogy, I’m happy to report that the tiger never got out of the cage.”

Second, my first PSA blood test – a test I will have twice a year for the rest of my days – showed .001… basically showing that there are no prostate cancer cells in my blood or body.

As for my level of activity, shortly after my surgery, I asked Dr. McGovern if he thought it was a reasonable goal to play in my beloved Lake Placid Grand Masters Lacrosse Tournament in early August – 12 weeks after surgery. He responded in the affirmative. That gave me something to shoot for. I did play in it – 9 games in three days – and while I can’t say I was at all-star level, I had a blast.

I’m feeling extremely grateful to the longtime friends who supported me and the new friends I made. My gratitude for having crossed paths with Dr. Francis McGovern (and his awesome team!) is boundless. I was about to offer the cliché that as good a surgeon as he is, he is an even better person. As sure as I am of this, the truth is that I’m not qualified to make such a statement because I really don’t know what it takes to be a great surgeon. I just know that he was straight with me throughout; he was supportive but firm. I decided to fully trust him without reservation, and this experience has taught me that there aren’t many people with whom I have done that, and that’s probably something I need to reconsider. Cancer is not something that I would wish on anyone, but it is something that can make you stronger providing you approach it head-on and trust others to help you get through it.

So, yeah, I’m feeling pretty good right now. However, I can’t help but wonder (and maybe it’s that man v. woman thing creeping in there) if I would still be writing this if:

– The margins were not clear?

– My PSA score was jacked up to the 4.4 it hit last winter?

– I was still wearing Depends? (I was able to put them away after two months.)

I honestly don’t know. I do know that this experience has changed me. And I think for the better. Time will tell. It always does.

I also know I’m grateful… really grateful.

Onward, Malcolm Gauld

Malcolm – Kevin has encouraged me to read about your experience with a prostate diagnosis. He sent it to me and I appreciate learning about your experience. In about a week I’m going to do radiation treatment of my prostate. The closer I get to the date, the more I think about it. You have helped me.

I’m now 83 and just got remarried in January to a wonderful woman. I’m a very fortunate person in many ways. Among them are living in a Continuous Care Community (read happy old folks), Janet and my wife like each other (Janet also lives here), and I’m in touch frequently with Andy (in Tokyo) and Kevin.

Hi, Peter – A bit embarrassing to note that I only just now saw your thoughtful note of three months ago. Hope your treatments have gone well! Feel free to contact me any time. Best to you and yours. – Malcolm