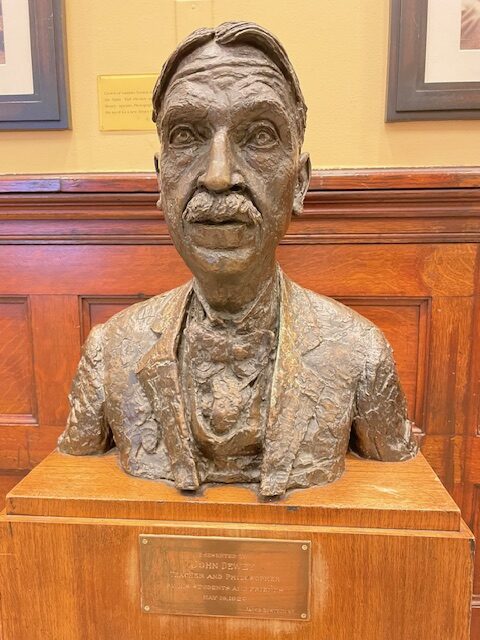

– with Apologies to John Dewey (1859-1952)

A half-century+ has passed since I spent a Maine summer as a college intern at the Hyde Summer School. Maybe it’s a good time to pause and share what I’ve got to show for my time as an educator.

Before launching into 10 Steps to the Schools We Want, a quick “if/then” note of caution: If you feel that we already have them, you may want to stop reading now.

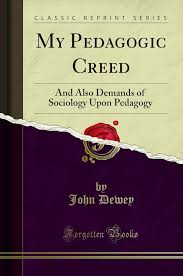

Over 125 years ago, philosopher educator John Dewey wrote My Pedagogic Creed. It presented about 80 “I believe…” statements like this one: I believe that education is the fundamental method of social progress and reform.

When I studied Dewey and his creed during my college years, this statement resonated deeply within. It still does. The following is both guided by and offered in its spirit. Without further adieu…

10 Steps to the Schools We Want

Point #1 — The Problem & The Solution in 15-second sound-bites:

The Problem: We care more about what they can do than about who they are and they know it. (They = the 50M students attending our schools.)

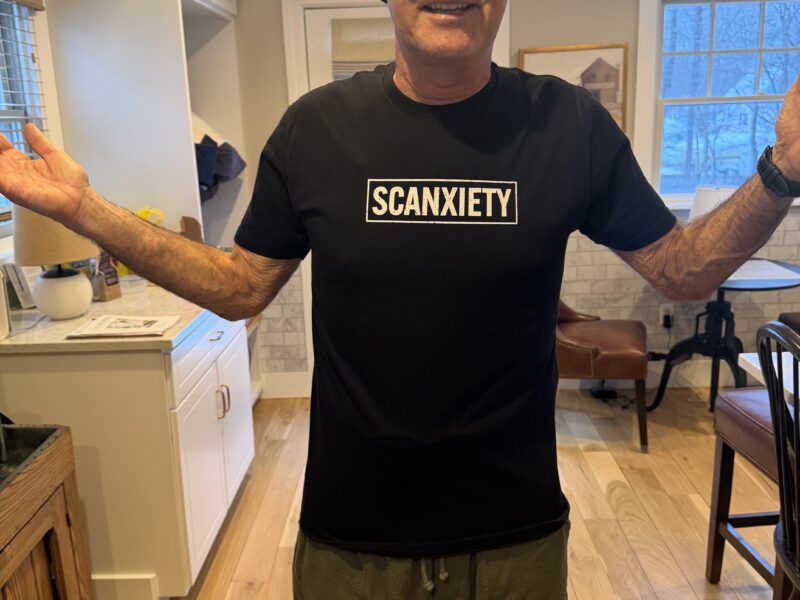

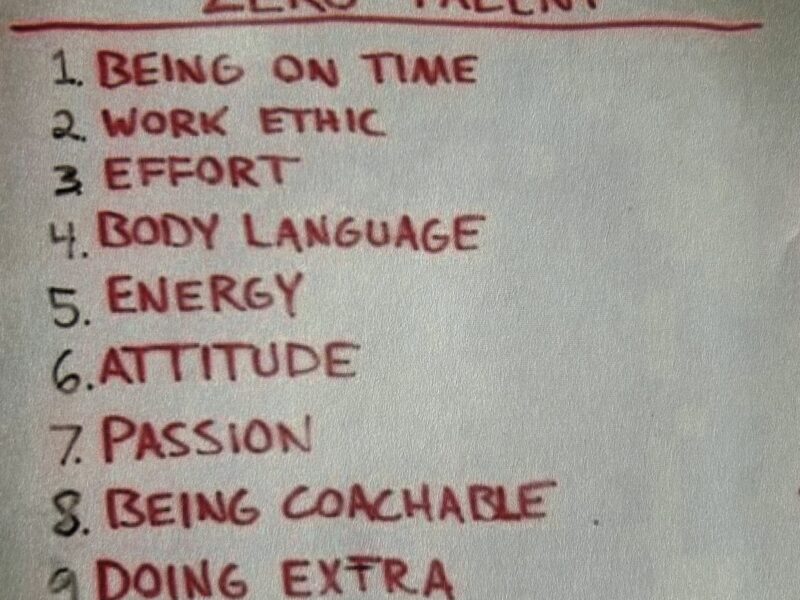

The Solution: Let’s flip those priorities and value attitude over aptitude… effort over ability… and character over talent. (Note Key Distinction: “over”… not… “instead of”)

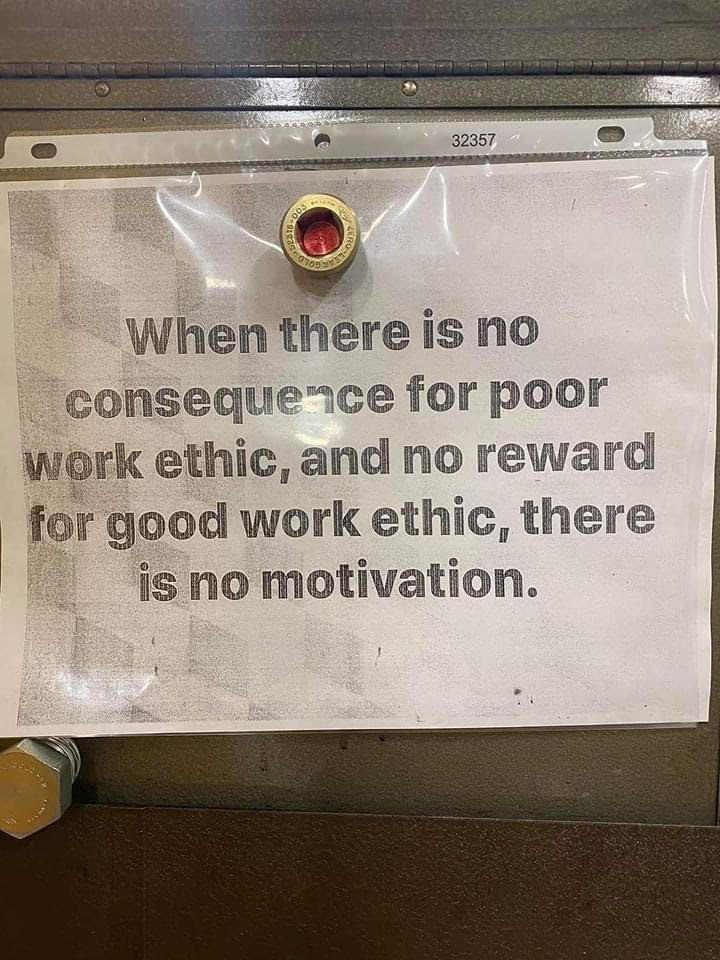

Posters and bumper stickers are all well and good, but they are useless if we do not ensure that these priorities are reflected in grading systems, rewards & discipline processes, and graduation requirements.

Point #2 — We Americans love the idea of reform… Actual Reform?… not so much.

The list of so-called school reforms we have adopted nationally that were going to save us is mind-boggling: New Math… Open Classrooms… Mainstreaming… Merit Pay… Magnet Schools… Back-to-Basics… Busing… Values Clarification… SEL… E-Learning… Special Ed and the ever-evolving alphabet soup of it’s offspring: ADD, ADHD, IEP, FAPE, ASD, ODD, etc… Experiential Learning… A Nation at Risk… No Child Left Behind… Common Core… Home-Schooling… Vouchers… Charters… etc. (And that’s the short list!) Nearly all of these end up fueling “The Problem” of Point #1 and too many serve the misguided, if perhaps unintentional, purpose of training kids to be better at school so they can qualify for more school. All too often, the programs we endorse and the measures we take end up reflecting what we adults want at the expense of what kids need.

Point #3 — “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” – Peter Drucker

There’s no getting around it: Every school has a culture. Here’s the question: Is Yours by design or default? Great schools deliberately envision, design, nurture, celebrate, and value an aspirational culture throughout each and every school day. Far too many schools let their culture happen to them. Of the many schools and organizations I have visited while developing the Discovery Process (DP), the ones with inspiring cultures invariably demonstrate three specific qualities in constant interaction with each other:

a) A core purpose or reason for existence. What Jim Collins calls a BHAG – Big. Hairy. Audacious. Goal. (e.g., Harvard = Ve Ri Tas… Bath Iron Works = “Through These Gates Pass the Best Shipbuilders in the World”… Rotary’s 4-Way Test) These aspirations are not just stated, but lived… by all stakeholders.

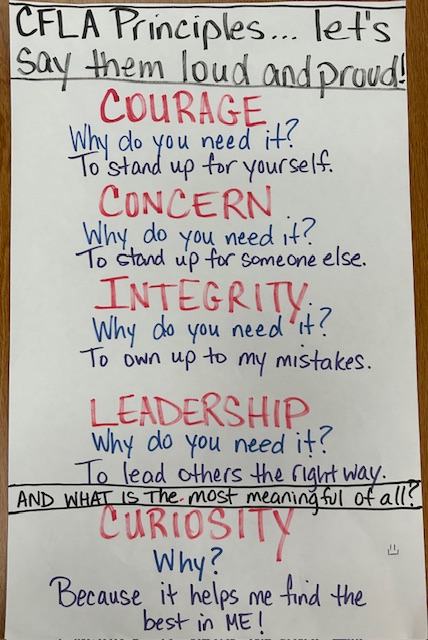

b) A common language that supports that BHAG. (e.g., Hyde’s 5 Words & Principles)

c) A set of practices and traditions that supports that core purpose and common language. (Hyde examples: auditions, faculty evaluations, the Happy. To. Do It. ethic.) The primary work of the DP is to help schools put culture first by turning their attention to these three qualities.

Point #4 — The kids must participate in their own resurrection.

Let’s face it: The kids are bummed. A 2022 CDC survey of 7,705 high school students revealed that 44% felt persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness that prevented them from participating in normal school activities. (A shocking 9% admitted to a suicide attempt — not ideation — an actual attempt.) The normal reaction of most schools to a problem like this is to double down on “us” (i.e., the adults). In other words, hire more counselors, create new student-centered adminstrative roles, or increase student access to professional therapists. These may well be good things to do, but… I submit that it’s time for the kids to be the major players in pulling themselves out of their “bummed-outness.” The DP intentionally places kids in roles where they act as leaders in this effort. This is not to say that it’s the only way. It is, however, offered as a deliberate break from adult-centric approaches common to past reform efforts.

Point #5 — Social & Emotional Learning (SEL) Demands Social & Emotional Teaching (SET)

Time will tell whether SEL is here to stay or is destined to join the above list of “reform” efforts that have come and gone. In all the effective SEL programs I have seen in operation, the teachers have reflected a “we’re not teaching subjects, we’re teaching students” ethos. For sure, there are forces at work that make it hard for teachers to transition from our national predominantly academic achievement system to more of a personal growth mindset — e.g., mandatory testing, teacher’s union regulations, over-zealous school boards — but these times in which we live cry out for it to an extent rendering the degree of difficulty irrelevant.

Point #6 — Parents Are the Primary Teachers… Home is the Primary Classroom

Or… Rarely Does Great Teaching Win Out Over Bad Parenting.

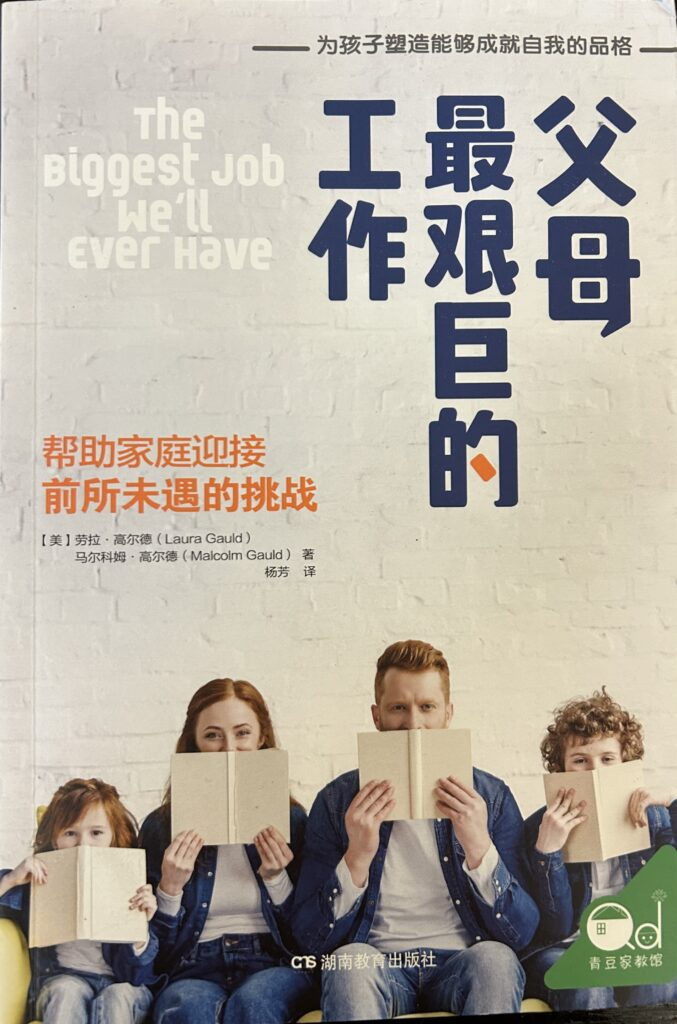

To borrow from ancient folk wisdom by way of NYU professor Jonathan Haidt: Do not prepare the road for the child, prepare the child for the road. People often ask me, “Since you started teaching in the 70s, have kids changed?” My response: “I don’t know that kids have changed all that much, but their parents have changed a lot!” Perhaps a story of my travels to China best presents Point #6.

A decade ago, I spent the better part of a day at a distinguished high school in Shenzhen. After a few hours, the head of school and I had developed a rapport that found us good-naturedly probing each other with challenging questions. (This was all through interpreters as neither of us spoke the other’s language.) At one point, my host provocatively observed, “You do know that we Chinese educators scoff at your American obsession with class size and faculty-student ratios?” I replied, “No, I did not. And why is that?’ He replied, “You must do that because you no longer have any discipline in your culture. Hence, we all wonder what you’re going to do when your obsession devolves to the point where it’s not financially feasible?”

Suppressing my reflexive nationalist sentiment, I asked, “What’s your average class size?” He responded, “52.” (In case you’re wondering, the U.S. national average is in the mid- to high-teens.) At that point we went on a school tour.

Sure enough, classroom after classroom revealed highly attentive students sitting among 50 or so of their peers, until… we opened the door to a classroom with one student fast asleep, his head buried in his arms on his desk. Seizing the moment to razz my host, I asked, “What about that young man’s discipline?” Without missing a beat, my host replied, “Oh, that’s no problem. We’ll just call his parents.” Sensing my puzzlement, he continued, “You see, in our country, the teacher’s job is to deliver the math; the parent’s job is to deliver the discipline. In your country, you make your teachers do both and you completely let your parents off the hook.” I replied, “You got me. I got no comeback for that.”

Thirty years ago, I was fortunate to study in residence on a fellowship at Teachers College, Columbia University. At one point, while studying the work of educator David Nyberg, we had a lively discussion relating to this quote from his writings: If parents do not contribute to the moral education of their own children, teachers cannot reasonably be expected to make up the deficit… Perhaps the first move in rethinking how we teach values in school is to impress on parents that they, and not teachers, are their children’s primary educators.… Yup… Suffice it to say that Nyberg’s prescience has only amplified in the three decades since that fellowship. Sorry for the unusual length of this particular point, but I will close with the assertion that it’s hard for me to imagine the other nine points happening with any lasting effect without renewed standards of productive attitudes and behaviors being expected on the home front.

Point #7 — The Power of Example

Another story from a foreign land: An American businessman is in Tokyo negotiating a business deal with a Japanese businessman. Breaking for lunch, they walk together to a restaurant. Stopping at a crosswalk, they wait for the light to change. Within seconds, the crosswalk fills with hordes of lunchbreakers, the entire crowd patiently waiting to cross the street. Only, at this particular moment, despite the fact that no cars are coming in either direction, the crowd continues to wait. At that point, the American turns to his Japanese counterpart and exclaims, “This is amazing! If we were in New York, Chicago, or LA, everyone would just be running across the street!” Surprised by the remark, the Japanese businessman calmly responds, “But, there could be a child watching.”

Looking out over our contemporary societal landscape, the extent to which we adults care about the examples we set for young people is at an all-time low. Perhaps we are inured given the constant barrage of news and social media outlets serving up questionable antics, words, and behaviors of politicians, pro athletes, celebrities, not to mention everyday people.

For example, my Sunday newspaper recently featured the following front page headlines:

Fights. Ejections. Irate fans. What’s going on in Maine high school sports?… In the article, the president of the Maine Principal’s Association (our state’s governing body for public high school sports) was quoted as follows: “There’s always been passion behind sports — that’s what makes it special — but I don’t remember on a night-in, night-out basis needing to address adult behavior… You talk to any athletic director and they’re going to have a story about having to remove fans.” (And he’s not talking about the kids!)

That same edition of that Sunday paper also presented a guest column from a highly respected girl’s lacrosse coach who doubles as a certified ice hockey official. He writes, “When I became certified as a hockey referee, I expected to learn about the rules and nuances of officiating. Instead, much of my training revolved around managing aggressive parents.”

We Mainers love our sports, but issues concerning the power of example are not unique to us. I recently watched various sports talk shows covering the story of a certain upper-stratospherically paid NBA star who had received multiple team suspensions due to his refusal to transition from starter to substitute, presumably as a ploy to be traded to another team. (His wish was ultimately granted.) Although I’m old enough to remember pro athletes holding down second jobs in the off-season, I “get” the fact that hard-nosed negotiation is integral to pro sports. My problem with this scenario? Not once did I hear a pundit raise the issue of how this might impact the attitudes and behaviors of his millions of young fans. To clarify: Years ago, there might have been argument over whether said example was, in fact, bad or not. Today, it simply does not come up at all as a matter of discussion.

Point #7 argues that we will not have the schools we want if the responsibility for substantive change lies solely within the schoolyard gates. We — as in Every. Single. One. Of. Us. — need to raise our game.

Point #8 — Bring Back More Local Control

My smalltown New England upbringing probably gave me a Norman Rockwell-ian view of the world, but I have always perceived a school principal or superintendent as someone who periodically looks out over their student body and surrounding community and asks, “OK, What does this particular group of students and their families in this particular community need from us at this particular time in order for us to help them prepare for successful and fulfilling futures?” After all, school districts only 20 miles apart might benefit from substantively different programs and emphases according to the needs of their respective constituencies. Since 2019, I have spoken with scores of public, private, and charter school operators about the possibility of implementing the Discovery Process. Heading into these discussions, I was not prepared for the sheer number of external mandates and directives school leaders must satisfy before they can even consider the internal needs uniquely specific to the students and families they serve. It’s time to return more local control to our schools.

Point #9 — Clarified Priorities

In light of Points #1, #2, and #3, the reader will not be surprised by my belief that school culture matters most of all. But we must mean it! One of the problems preventing schools from taking this step is the simple fact that I have never had any school leader tell me that they didn’t feel culture is essential. In fact, some will even profess that it’s the most important element of their school. At the same time, some of these very same educators will think nothing of spending $60-to-$80K on a program designed to improve math or reading scores while they balk at spending 10% of that amount on a culture improvement program. (And, Yes, I get the fact that many of them are being judged, promoted, compensated, and even fired according to how well their students perform on standardized tests.) It’s time to walk the walk. Time to put our $$$s where our mouths are.

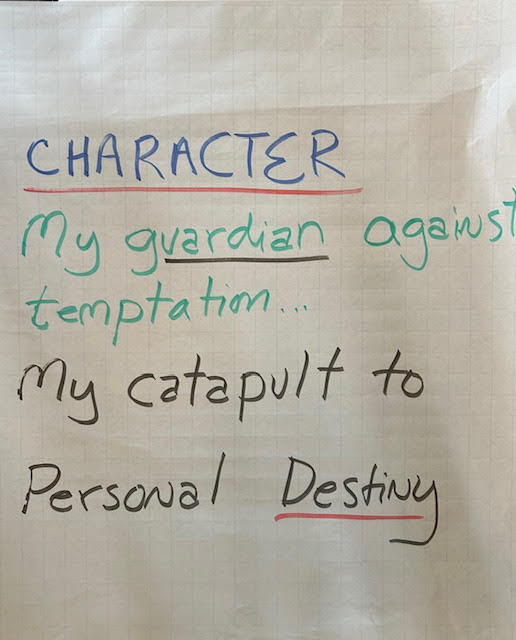

Point #10 What is Character?

Q: OK, Malcolm, you’ve talked a lot about character, but you haven’t told us what it is.

A: Character is that inner voice that serves as our guardian against temptation and our catapult to greatness.

My definition, informed by people, readings, and experiences during my pedagogic journey, perceives character as a dual force. By greatness, I don’t mean in comparison to everybody else. I refer to personal best. Many character ed programs are heavy on the guardian part of the equation — “Hey, maybe these kids will stop bullying each other if we throw a character program into our mix.” — and light on the catapult part… the most exciting part! (If you like what character ed can do to counter bullying, you’ll love how it can help kids go “from good to great!”) At risk of understatement, the notion that character ed is for all does not break new ground. It goes back at least to 500 BC when ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus summed it up in three words: “Character is destiny.”

And if it is indeed true that each of us has a date with a unique personal destiny, character development is the vehicle that can take us there. Without it, we’re left standing by the side of the road wondering why our ride has yet to show up.

Onward, Malcolm Gauld