Hyde-Woodstock teacher Robert Tunney recently passed along a fascinating blog article by Heidi Grant Halvorson from the Harvard Business Review web site. Check out this excerpt:

People with above-average aptitudes — the ones we recognize as being especially clever, creative, insightful, or otherwise accomplished — often judge their abilities not only more harshly, but fundamentally differently, than others do (particularly in Western cultures). Gifted children grow up to be more vulnerable, and less confident, even when they should be the most confident people in the room. Understanding why this happens is the first step to righting a tragic wrong. And to do that, we need to take a step back in time.

Chances are good that if you are a successful professional today, you were a pretty bright fifth-grader. You did well in several subjects (maybe every subject), and were frequently praised by your teachers and parents when you excelled.

When I was a graduate student at Columbia, my mentor Carol Dweck and another student, Claudia Mueller, conducted a study looking at the effects of different kinds of praise on fifth-graders. Every student got a relatively easy first set of problems to solve and were praised for their performance. Half of them were given praise that emphasized their high ability (“You did really well. You must be really smart!”). The other half were praised instead for their strong effort (“You did really well. You must have worked really hard!”).

Next, each student was given a very difficult set of problems — so difficult, in fact, that few students got even one answer correct. All were told that this time they had “done a lot worse.” Finally, each student was given a third set of easy problems — as easy as the first set had been — in order to see how having a failure experience would affect their performance.

Dweck and Mueller found that children who were praised for their “smartness” did roughly 25% worse on the final set of problems compared to the first. They were more likely to blame their poor performance on the difficult problems to a lack of ability, and consequently they enjoyed working on the problems less and gave up on them sooner.

Children praised for the effort, on the other hand, performed roughly 25% better on the final set of problems compared to the first. They blamed their difficulty on not having tried hard enough, persisted longer on the final set of problems, and enjoyed the experience more.

It’s important to remember that in Dweck and Mueller’s study, there were no mean differences in ability between the kids in the “smart” praise and “effort” praise groups, nor in past history of success — everyone did well on the first set, and everyone had difficulty on the second set. The only difference was how the two groups interpreted difficulty — what it meant to them when the problems were hard to solve. “Smart” praise kids were much quicker to doubt their ability, to lose confidence, and to become less effective performers as a result.

The kind of feedback we get from parents and teachers as young children has a major impact on the implicit beliefs we develop about our abilities — including whether we see them as innate and unchangeable, or as capable of developing through effort and practice. When we do well in school and are told that we are “so smart,” “so clever,” or “such a good student,” this kind of praise implies that traits like smartness, cleverness, and goodness are qualities you either have or you don’t. The net result: when learning something new is truly difficult, smart-praise kids take it as sign that they aren’t “good” and “smart,” rather than as a sign to pay attention and try harder.

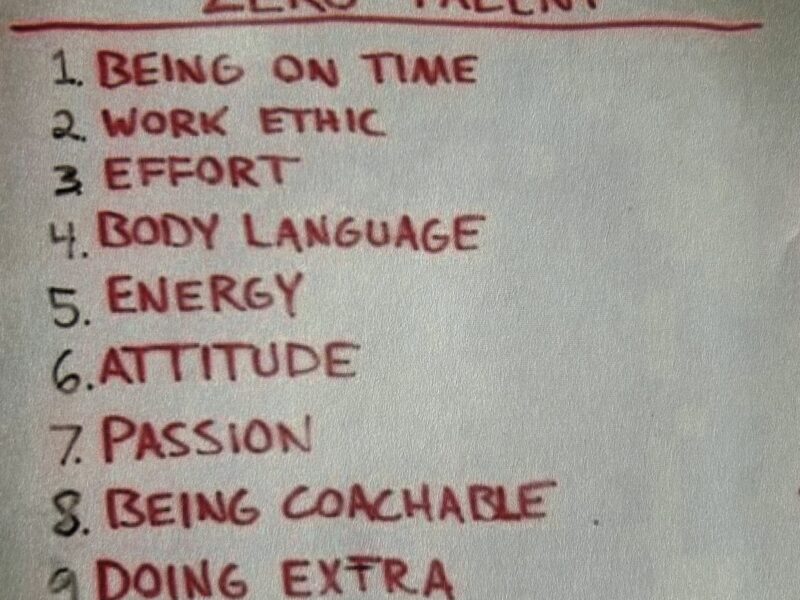

If you gave me a fifteen-second soundbite to describe our national educational ills, I would say, “The problem is that we care more about what they can do than ab0ut who they are… and they know it.”

Give me fifteen seconds more to outline the solution and I would say, “Let’s switch our emphasis from aptitude to attitude, from ability to effort, and talent to character.”

I might also have them read this article. Here’s Halverson’s conclusion:

No matter the ability — whether it’s intelligence, creativity, self-control, charm, or athleticism — studies show them to be profoundly malleable. When it comes to mastering any skill, your experience, effort, and persistence matter a lot. So if you were a bright kid, it’s time to toss out your (mistaken) belief about how ability works, embrace the fact that you can always improve, and reclaim the confidence to tackle any challenge that you lost so long ago.

Yup.

Onward, Malcolm Gauld

PS: Here’s the link: http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2011/11/the_trouble_with_bright_kids.html?cm_sp=most_widget-_-default-_-The+Trouble+With+Bright+Kids